If there is one phrase that keeps appearing in almost every serious discussion about amphibian decline, it’s this: chytrid fungus.

Often shortened to “Bd”, this microscopic pathogen has been described by scientists as the most destructive wildlife disease ever recorded. Entire frog populations have vanished in a matter of years — sometimes before researchers even realised they were at risk.

In the first article of this series, we looked at why frogs are disappearing worldwide. Here, we’re zooming in on the single factor that has reshaped amphibian life more than any other in modern history.

What exactly is chytrid fungus (Bd)?

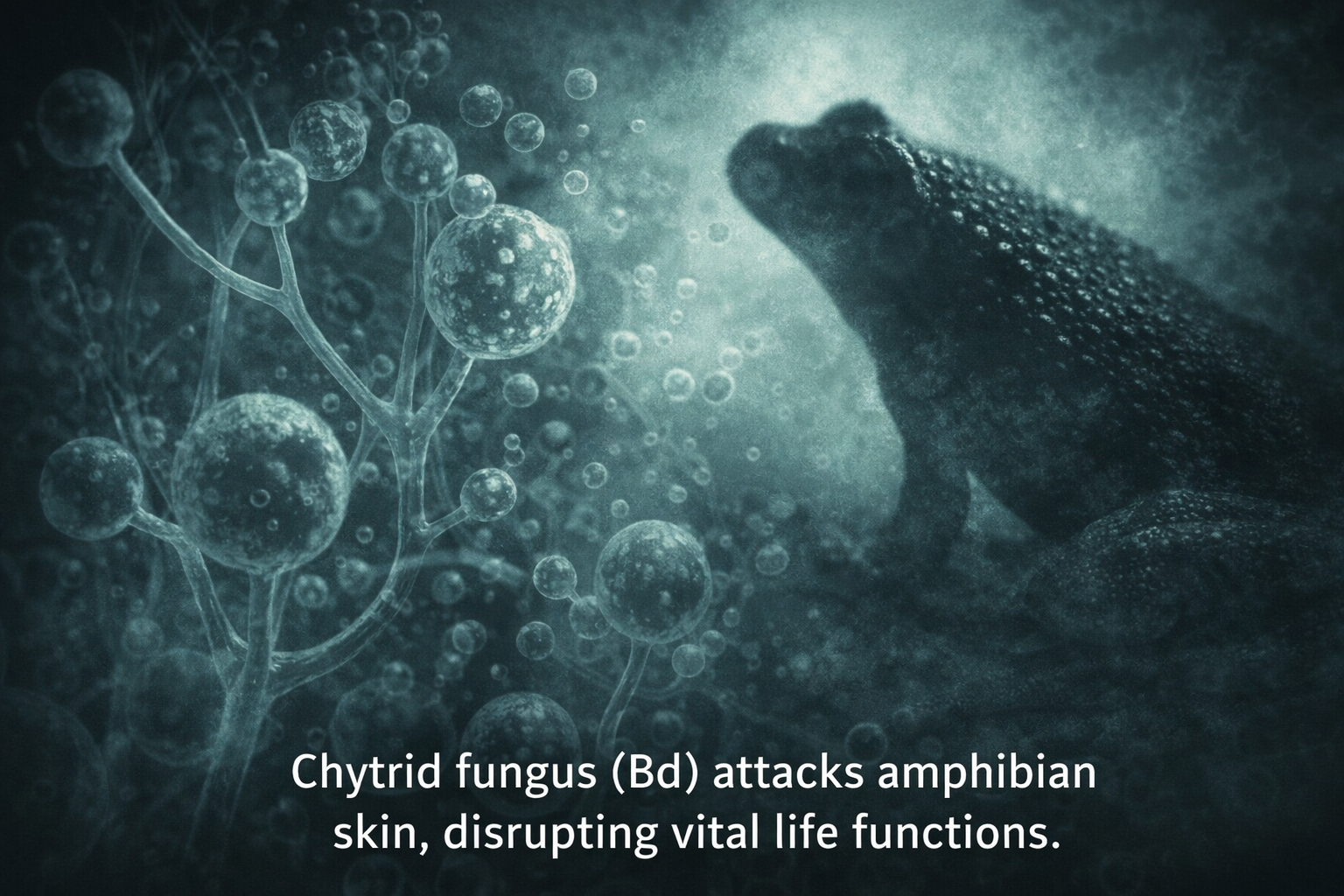

Chytridiomycosis is caused by the fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, usually referred to as Bd. Unlike many fungi, Bd is specialised — it targets amphibians and, more specifically, their skin.

That matters because frog skin isn’t just a protective layer. It’s involved in:

- oxygen exchange

- hydration

- electrolyte balance

When Bd infects the skin, it interferes with all of these processes at once. In severe cases, frogs die from cardiac arrest caused by electrolyte imbalance — not from “infection” in the way people usually imagine it.

The scale of the damage

According to reporting summarised by SciTechDaily, Bd has been linked to declines in hundreds of amphibian species across every continent where frogs occur.

Some species have been pushed to extinction. Others survive only in tiny, isolated populations — or in captive assurance colonies.

What makes Bd particularly dangerous is not just how lethal it can be, but how quickly it spreads once it enters a new area.

Tracing Bd back to its source

One of the most important recent breakthroughs has been identifying where the most aggressive strains of Bd likely came from.

Research covered by SciTechDaily points to Brazil as a key origin point for a highly virulent lineage of Bd, which then spread globally via human activity — particularly through the movement of amphibians for food, pets, and research.

This doesn’t mean “Brazil caused the problem”. It means global trade unintentionally created perfect conditions for a pathogen to move far beyond its original ecological context.

Why some frogs survive (and others don’t)

One of the most frustrating aspects of Bd is that its impact is uneven.

Some species crash almost immediately. Others persist, even in Bd-positive environments. Scientists believe this variation comes down to a mix of factors:

- skin microbiomes (beneficial bacteria that inhibit Bd)

- local climate and temperature

- genetic resistance

- behaviour and habitat use

In other words, Bd doesn’t act alone — it interacts with the environment and the frog’s own biology in complex ways.

What this means for keepers and breeders

For people who keep frogs, Bd isn’t an abstract concept. It’s a real-world biosecurity issue.

Good practice matters:

- quarantining new arrivals

- not sharing equipment between enclosures without cleaning

- being cautious about wild-collected materials

Responsible captive keeping isn’t just about animal welfare — it plays a role in preventing accidental disease spread.

Is there any good news?

Yes — cautiously.

Some frog populations appear to be stabilising, particularly where Bd-resistant individuals survive long enough to reproduce. In other cases, habitat management and reduced environmental stress seem to improve survival rates.

There’s also growing recognition that conservation can’t rely solely on protected reserves. As we’ll explore next, private land and citizen science are becoming unexpectedly important refuges.

- Why Private Land Is Becoming the Last Refuge for Rare Frogs

- A New Poison Dart Frog Species Discovered From a 60-Year-Old Specimen

Sources

- SciTechDaily: “Deadly Frog Fungus Devastating Amphibians Worldwide Traced Back to Brazil”

- Techno-Science: Global Amphibian Decline Overview

Previously: Why Frogs Are Disappearing Worldwide